Poem

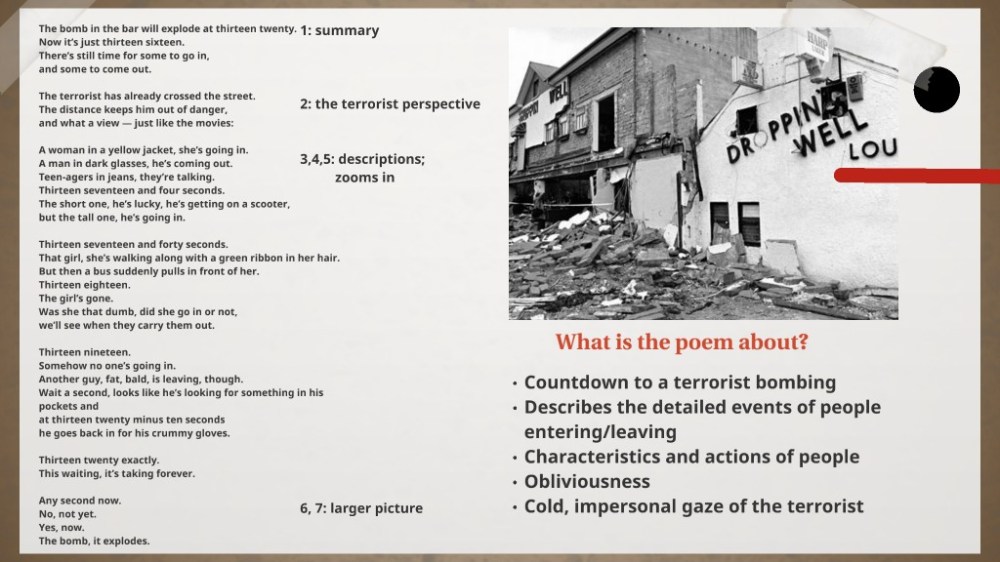

The bomb in the bar will explode at thirteen twenty.

Now it’s just thirteen sixteen.

There’s still time for some to go in,

and some to come out.

The terrorist has already crossed the street.

The distance keeps him out of danger,

and what a view -just like the movies:

A woman in a yellow jacket, she’s going in.

A man in dark glasses, he’s coming out.

Teen-agers in jeans, they’re talking.

Thirteen seventeen and four seconds.

The short one, he’s lucky, he’s getting on a scooter,

but the tall one, he’s going in.

Thirteen seventeen and forty seconds.

That girl, she’s walking along with a green ribbon in her hair.

But then a bus suddenly pulls in front of her.

Thirteen eighteen.

The girl’s gone.

Was she that dumb, did she go in or not,

we’ll see when they carry them out.

Thirteen nineteen.

Somehow no one’s going in.

Another guy, fat, bald, is leaving, though.

Wait a second, looks like he’s looking for something in his pockets and

at thirteen twenty minus ten seconds

he goes back in for his crummy gloves.

Thirteen twenty exactly.

This waiting, it’s taking forever.

Any second now.

No, not yet.Yes, now.

The bomb, it explodes.

Poetess

Well-known in her native Poland, Wisława Szymborska received international recognition when she won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1996. In awarding the prize, the Academy praised her “poetry that with ironic precision allows the historical and biological context to come to light in fragments of human reality.” Collections of her poems that have been translated into English include People on a Bridge (1990), View with a Grain of Sand: Selected Poems (1995), Miracle Fair (2001), and Monologue of a Dog (2005).

Readers of Szymborska’s poetry have often noted its wit, irony, and deceptive simplicity. Her poetry examines domestic details and occasions, playing these against the backdrop of history. In the poem “The End and the Beginning,” Szymborska writes, “After every war / someone’s got to tidy up.”

In the New York Times Book Review, Stanislaw Baranczak wrote, “The typical lyrical situation on which a Szymborska poem is founded is the confrontation between the directly stated or implied opinion on an issue and the question that raises doubt about its validity. The opinion not only reflects some widely shared belief or is representative of some widespread mind-set, but also, as a rule, has a certain doctrinaire ring to it: the philosophy behind it is usually speculative, anti-empirical, prone to hasty generalizations, collectivist, dogmatic and intolerant.”

Szymborska lived most of her life in Krakow; she studied Polish literature and society at Jagiellonian University and worked as an editor and columnist. A selection of her reviews was published in English under the title Nonrequired Reading: Prose Pieces (2002). She received the Polish PEN Club prize, the Goethe Prize, and the Herder Prize.

Analysis

“The Terrorist, He’s Watching” by Wislawa Szymborska is a poem that tells about the narrator waiting anxiously for a planted bomb to explode in a bar, watching and describing people as they enter and leave the bar. When a person leaves, the narrator acts as though that person is going to miss a real treat; when a person enters the bar, the tone of the narrator seems to increase, as though all of those to experience the bomb are quite lucky indeed.

The speaker of the poem, at first, seems to be that of an accomplice to the terrorist or someone who just happens to be watching and understanding what is going on – perhaps the person that has ordered the terrorist to leave the bomb. This can be seen in lines 1-7, when the narrator is describing the movements and actions of the terrorist, noting how he is now safe from the blast of the bomb. It is more likely that this first narrator is an accomplice, or someone on the inside of the job, as, in the first line, they state the time that the bomb is supposed to go off in the bar.

After the second stanza of the poem, the narrator seems to be the terrorist himself, watching eagerly as people go in and out of the bar, counting down the minutes until his bomb is supposed to go off. This can be seen from the second stanza and until the end of the poem, as the narrator now seems a little more aware of what is going on, keeping the countdown by every minute and every second. The feelings of the narrator are more pronounced – he becomes disappointed as people go on – “Was she that dumb did she go in, or not?

And more pleased when they leave – “The short one, he’s lucky, he’s getting on a scooter”. The role of narrator seems to change as each person is able to get a better view of what is going on inside of the bar. The accomplice took over first, as the terrorist was busy setting the bomb, then, once the narrator was outside of the bar, he was able to take over and see what was happening.

As readers, we are able to know what he was thinking, what he was planning, and the numerous things he was feeling as a set to put his plan in motion to kill. Due to the use of the first person narrative, we were able to experience his emotions almost first hand; it was though the narrator was telling us, face-to-face, the ordeal he went through to assure the old man’s death. The use of first person allows us to become closer to the narrator, close enough to understand what he is doing.That is the magic of the first person narrative – we are able to experience everything firsthand, as though we were accompanying the protagonist.

What is the poem about?

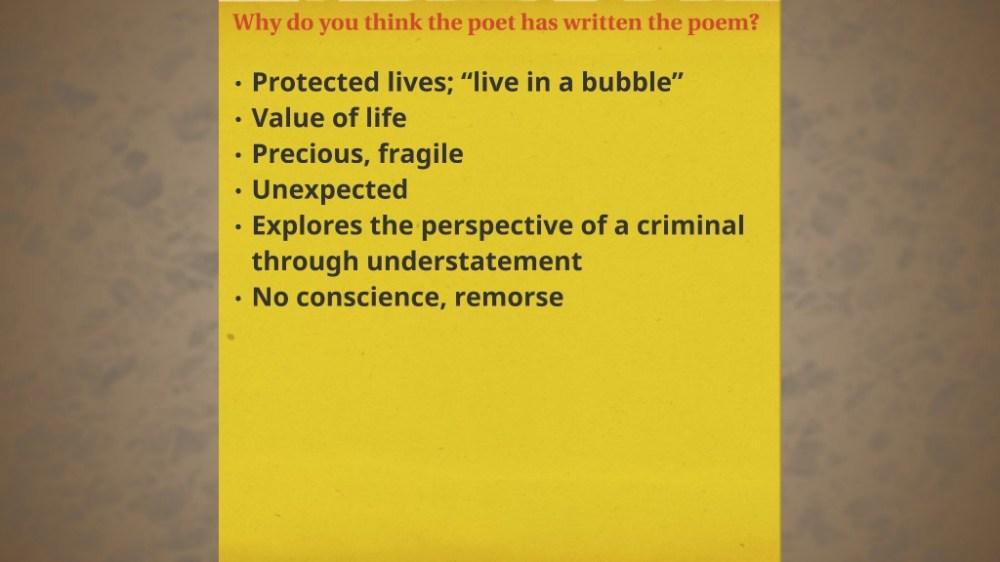

Why did the poet wrote the poem?

Who is speaking and to whom?

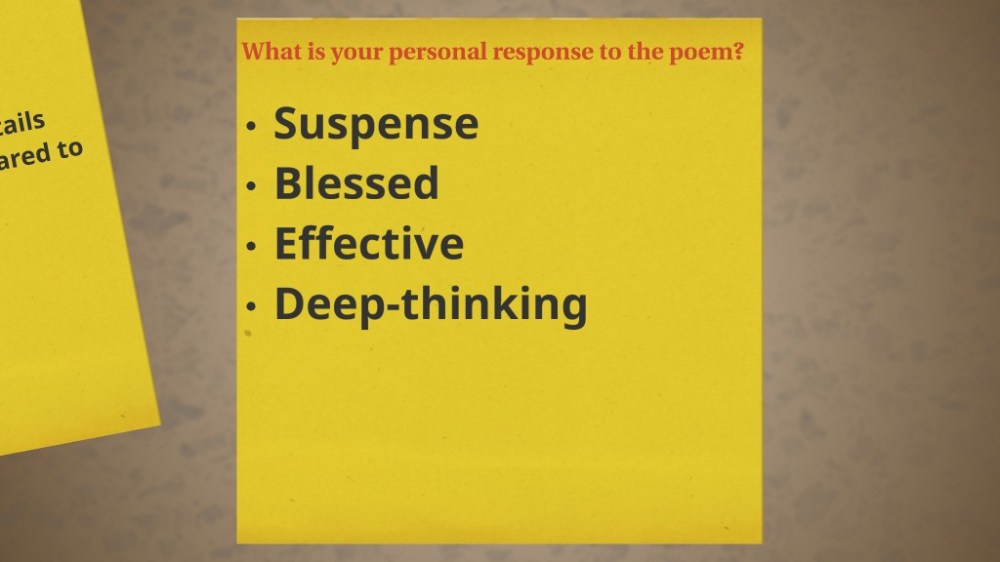

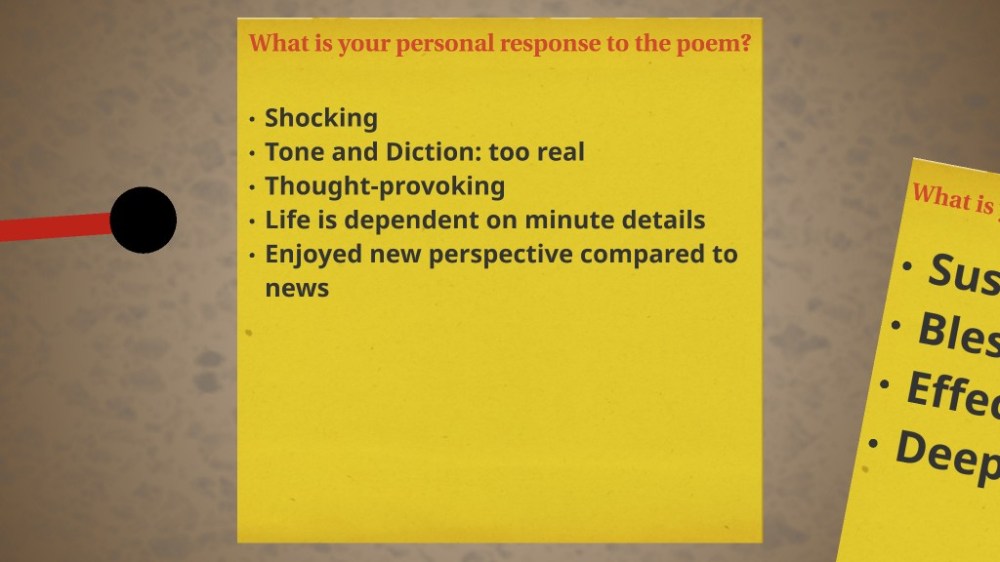

What might be your personal response to the poem?

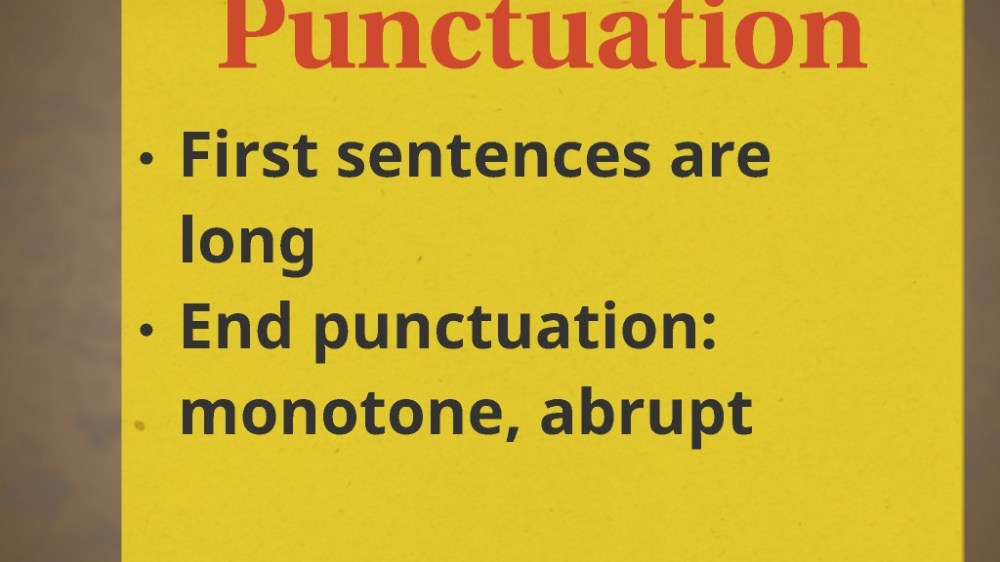

In what way the poem is written?

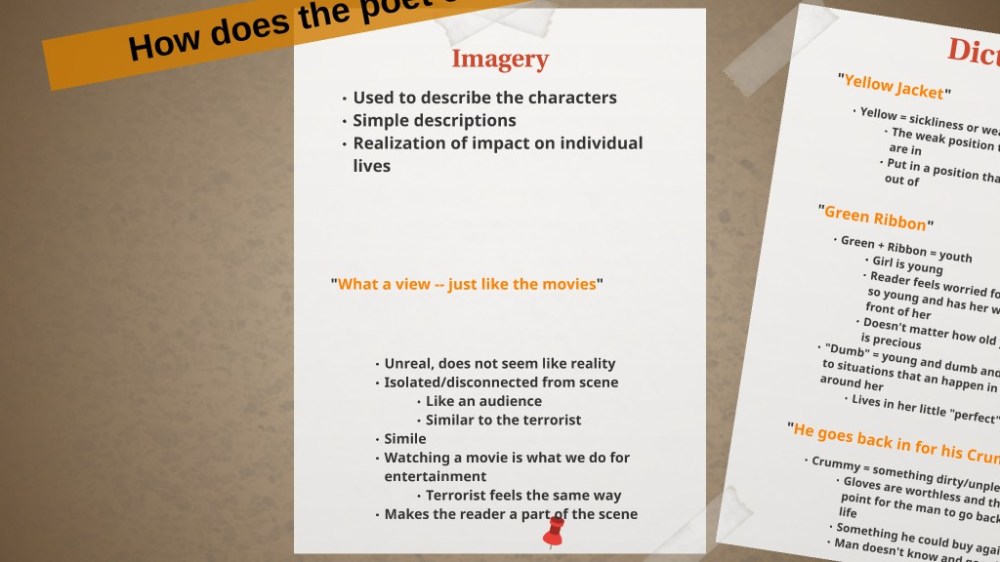

Literary devices