It was then she saw the wave. “Oh my God, the sea’s coming

in.” That’s what she said. I looked behind me. It didn’t seem that

remarkable. Or alarming. It was only the white curl of a big wave.

But you couldn’t usually see breaking waves from our room.

You hardly noticed the ocean at all. It was just a glint of blue above

that wide spread of sand that sloped sharply down to the water. Now

the froth of a wave had scaled up this slope and was nearing the tall

conifers that were halfway between our room and the water’s edge,

incongruous those trees in this lanscape of brittle thorny scrub. This

was peculiar. I called out to Steve in the bathroom. “Come out, Steve,

I want to show you something odd.” I didn’t want him to miss this.

I wanted him to come out quick before all this foam dissoved. “In a

minute,” Steve muttered, with no intention of rushing out.

Then there was more white froth. And more. Vik was sitting by the black door reading rhe first page of The Hobbit. I told him to shut

that door. It was a glass door with four panels, and he closed each one,

then came across the room and stood by me. He didn’t say anything, he

didn’t ask me what was going on.

The foam turned into waves. Waves leaping over the ridge

where the beach ended. This was not normal. The sea never came this

far in. Waves not receding or dissolving. Closer now. Brown and gray.

Brown or gray. Waves rushing past the conifers and coming closer to

our room. All these waves now, charging, churning. Suddenly furious.

Suddenly menacing. “Steve, you’ve got to come out. Now.” Steve ran

out of the bathroom, tying his sarong. He looked outside. We didn’t

speak.

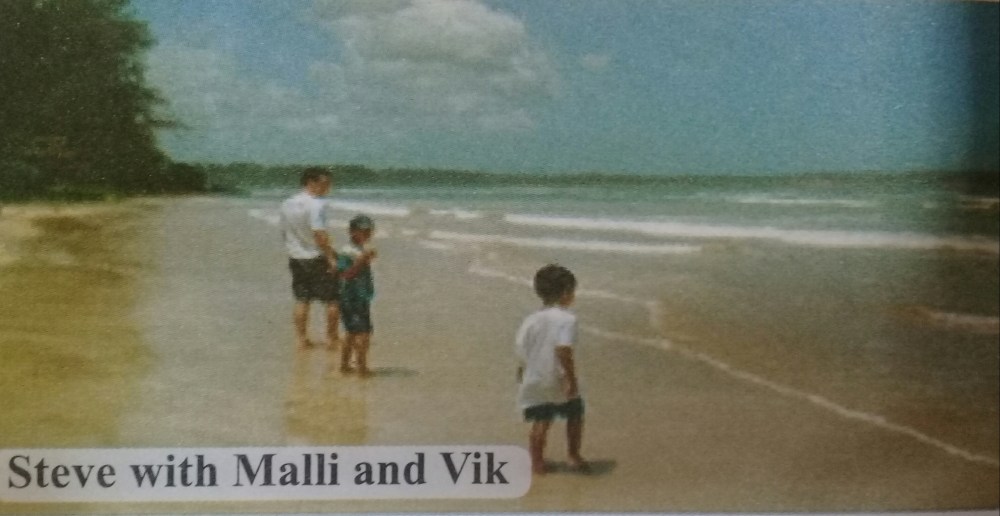

I grabbed Vik and Malli, and we all ran out the front door. I was

ahead of Steve. I held the boys each by the hand. “Give me one of them.

Give me one of them,” Steve shouted, reaching out. But I didn’t. That

would have slowed us down. We had no time. We had to be fast. I knew that. But I didn’t know what I was fleeng from.

I didn’t stop for my parents. I didn’t stop to knock on the door

of my parents’ room, which was next to ours, on the right as we ran out.

I didn’t shout to warn them. I didn’t bang on their door and call them

out. As I ran past, for a splintered second, I wondered if I should. But

I couldn’t stop. It will stall us. We must keep running. I held the boys

tight by their hands. We have to get out.

ran as fast as I did. They didn’t stumble or fall. They were barefoot,

but they didn’t slow down because stones or thorns were hurting them.

They didn’t say a word. Our feet were loud, though. I could hear them,

slamming the ground.

Ahead of us a jeep was moving, fast. Now it stopped. A safari

jeep with open back and sides and a brown canvas hood. This jeep was waiting for us.We were all inside now. Steve had Vik on his lap, I

sat across from them with Mail on mine. A man was driving the jeep. I

didn’t know who he was.

Now I looked around me and nothing was unusual. No frothing

waters here, only the hotel. It was all as it should be. The long rows of rooms with clayed tiled roof, the dusty, orange-brown gravel driveway thick with wild cactus on both

sides. All there. The waves must have receded, I thought.

I hadn’t seen Orlantha run with us, but she must have done. She

was in the jeep. Her parents had rushed out of their rooms as we came

out of ours, and now her father, Anton, was with us too. Orlantha’s

mother, Beulah, was hoisting hereself into the jeep and the driver

revved the engine. The jeep jerked forward and she lost her grip, fell

off. The driver didn’t see this. I told him to stop, I kept yelling to him

that she had fallen out. But he kept going. Beulah lay on the driveway

and looked up at us as we pulled away. She half- smiled, in confusion

it seemed.

Anton leaned out the back to reach Beulah and drag her up.When he couldn’t, he jumped out. They were both lying on the gravel now, but I didn’t call out to the driver to wait for them. He was driving very fast. He’s right, I thought, we have to keep moving. Soon we will be away from the hotel.We were leaving my parents behind. I panicked now. If I had screamed at their door as we ran out, they could have run with us. “We didn’t get Aachchi and seeya,” I yelled to Steve. This made Vikram cry. Steve held on to him, clasping him to his chest. “Aachchi and seeya will be okay, they will come later, they will come,” Steve said. Vik stopped crying and snuggled into Steve.

I was thankful for Steve’s words, I was reassured. Steve is right.There are no waves now. Ma and Da, they will walk out of their room. We will get out of here first, and they’ll join us.I had an image of my father walking out of the hotel, there were puddles everywhere, he had his trousers rolled up. I’ll ring Ma on her mobile as soon as I get to a phone, I thought.

We were nearing the end of the hotel driveway. We were about to turn left onto the dirt track that runs by the lagoon.Steve stared at the road ahead of us.Ge kept banging his kneel on the floor of the jeep.Hurry up, get a move on.

The jeep was in water then. Suddenly, all this water inside the jeep. Water sloshing over our knees. Where did this water come from? I didn’t see those waves get to us. This water must have burst out from beneath the ground. What is happening? The jeep moved forward slowly. I could hear its engine straining, snarling. We can drive through this water, I thought.We were tilting from side.The water rising now, filling the jeep.

It came up to our chests. Steve and I lifted the boys as high as we could. Steve held Vik, I had Mal. Their faces above the water, the tops of their heads pressing against the jeep’s canvas hood, our hands tight under

their armpits.The jeep rocked. It was floating, the wheels no longer gripping the ground. We kept steadying ourselves on the seats. No one spoke. No one uttered a sound.

Then I saw Steve’s face. I’d never seen him like that before. A sudden look of terror, eyes wide open, mouth agape. He saw somethingbehind me that I couldn’t see. I didn’t have time to turn around and look.

Because it turned over. The jeep turned over. On my side. Pain. That was all I could feel. Where am I? Something was Crushing my chest. I am trapped under the jeep, I thought, I am being flattened by it. I tried to push it away, I wanted to wriggle out, But it was too heavy, whatever was on me, the pain unrelenting in my chest.

I wasn’t stuck under anything. I was moving, I could tell now. My body was curled up, I was spinning fast. Am I underwater? It didn’t feel like water, but it has to be, I thought. I was being dragged along, and my body was whippingbackwards and forwards. I couldn’t stop myself. When at times my eyes opened, I couldn’t see water. Smoky and gray.

Analysis

Deraniyagala begins her story by describing the morning of the tsunami. She, her family, and her parents were staying at the Yala Safari Beach Hotel on December 26, 2004, where they had spent several days during the Christmas holiday. They planned to return to her parents’ house later that day. With little warning, the tsunami overtook the beachfront area of the national park.

Deraniyagala describes the horror on her husband’s face just before the tsunami flipped the Jeep in which they were trying to outrun the strangeness they had noticed in the ocean. Deraniyagala was carried along with the churning water until she managed to grab onto a branch. This branch kept her from being swept out to the ocean in the receding waters.

From this point, Deraniyagala describes how she seemed to know her family was dead even though she did not yet have proof. She was in shock as she waited in the hospital for news. A friend finally took her to her aunt’s house in Colombo.

Deraniyagala found out in only a few days that her parents and oldest son had died in the wave but it was nearly four months before she got confirmation that her husband and youngest son were dead. Her first months after the tsunami were a blur of grief and pain. Deraniyagala abused herself by using drugs and alcohol to numb her pain.

Deraniyagala slowly made progress in her process of healing as she first visited her parents’ home in Colombo and then returned to London. It was nearly four years after the tsunami before Deraniyagala was able to go into the home she shared with her family in London.

Although she suffered a setback when she first traveled to New York City, Deraniyagala discovered that the city was a good choice to help her deal with her grief. At first, the city gave her a place where she was distanced from the things that reminded her of her family. As time went by, Deraniyagala realized she could better rediscover her family from the safety of that distance. She ends her story telling her reader she can hear her boys, at the age they would have been seven years after the tsunami, laughing in their garden in London.