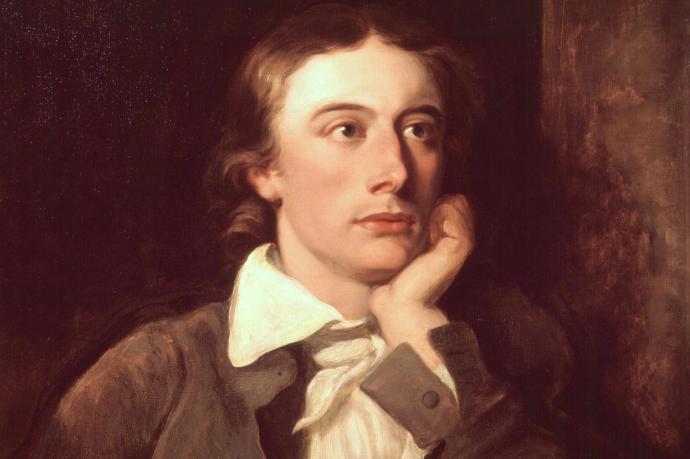

Poet-John Keats

John Keats

Overall Summary

Shelley’s sonnet wasn’t published until 1876 but Hunt’s appeared in 1818 (which is somewhat unfair since Hunt both ran a magazine and had more connections).

Analysis

“Son of the Old Moon-Mountains African”

The sonnet, To The Nile, by John Keats begins with the line “Son of the Old Moon-Mountains African!” Through this line, the poet characterizes the Nile River as the “son” of the old African Moon-Mountains. That is to say, The Nile has its origin from the Moon Mountains quite like the River Mahaweli has its origin from the Sri Pada or the Adams Peak Mountain.

In this line, the poet uses the poetic technique of inversion wherein the word order is inverted or changed. Here you can see the inverted position of the adjective “African”. Grammatically, an adjective normally comes before the main noun, here it is, Moon-Mountains.

Besides, the poet also uses another technique of personification, that is; the river here is personified as the son of the Moon-Mountains which are like parents.

“Chief of the Pyramid and Crocodile”

In the next line, the Nile is called as the Chief of the Pyramid and Crocodile. The mention of Pyramid and Crocodile relates to the ancient Egyptians who would build pyramids as tombs for their kings and queens. They built these tombs with huge blocks of stones and transported them through the Nile River in barges to the pyramid sites. It might not have been possible otherwise to carry these stone blocks through the rugged desert lands spread hundreds of miles. Thus, the poet rightly calls the Nile, the Chief of the pyramids.

Now let’s talk about the crocodiles, you might know that there is world’s largest species of crocodiles in River Nile, especially its banks which abound these huge crocodiles. These crocodiles are also considered to be the God Osiris legends. Though it isn’t clear if the poet has used hyperbole or exaggeration in this line, he certainly has used the technique of contrast, for example the Pyramids, which are non-living things whereas the crocodiles are living things.

“We call thee fruitful, and that very while”

In the third line of this sonnet, the poet calls the Nile fruitful as the river is said to sustain life in the Nile Valley not just through food from fishing and agriculture but also by giving them a kind of transport and also by working as a playground for water sports. The Nile itself is a symbol of fertility and prosperity.

“A desert fills our seeing’s inward span”

The third line says same as the fourth line. The poet through this line refers to his imagination which is filled with a desert. Imagination is at times called the “third eye” but the poet here refers it to “seeing’s inward span”. In fact this line indicates that our imagination consists of a desert whereas we are awe-struck at the fruitfulness of the river. So, barrenness and fruitfulness are correlated. They are in fact considered to be another wonder of nature.

“Nurse of swart nations since the world began”

Through the next line, the poet means that the river Nile, since time immemorial, has been nourishing and providing food to the dark nations or the Africans. Not only has The Nile River provided life to one country but to a number of countries whereby it flows.

“Art thou so fruitful? or dost thou beguile

Such men to honour thee, who, worn with toil,

Rest for a space ‘twixt Cairo and Decan?”

The next line of this sonnet begins with a rhetorical question which is also followed by another rhetorical question. Here the poet perhaps refers to temples built for Osiris which are stretched along the banks of the River.

The poet here wonders if the river Nile, through her magical charm, can make people believe and regard it as a holy river, such as the Ganges River in India. The poet also says that the river has a rest between Cairo and Decan. Where in Cairo the river ends in Decan it begins.

Keats, So far (in the octave), has reverently or respectfully treated the Nile. However, as the line number 9 begins with the sestet, we notice a ‘volta’ or a turn in the line of thought: The poet’s outlook to the Nile River gets changed from one of reverence to a realistic one.

“O may dark fancies err! They surely do“

Through this line, the poet says that imagination or fancy can mislead us. Here we find Keats criticizing his own habit of day-dreaming or ‘negative capability’. So, the poet now starts doubting his “dark fancies” or his romantic fancy which carried him to the exotic lands of ancient Egypt of Pyramids, Pharaohs and the great Nile steeped in legends. The poet now becomes more ‘down-to-earth’ and starts exploring the River from an aesthetic or artistic viewpoint.

“Tis ignorance that makes a barren waste

Of all beyond itself…”

In the above line, the poet wonders at his own ignorance or the ignorance of the Europeans whose ‘dark fancies’ about Africa mainly contained giant pyramids and long-stretched deserts. The poet, through the same line, even asks: “Art thou so fruitful?” Keats says his obsession with desert is as a result of the ‘ignorance’ of Nile valley’s fertility. He believes that the landscape is so fertile that it was claimed to have given birth to the first human civilization.

“Thou dost bedew

Green rushes like our rivers, and dost taste

The pleasant sunrise. Green isles hast thou too,

And to the sea as happily dost haste.”

The poet, in these lines, starts viewing the River in all its splendid beauty when it majestically journeys or flows from its home to the sea. Here he likens the Nile to “our rivers” whose plants with long leaves or green rushes have been beautifully decked up with drops and dew of mist This beautiful visual image appeals to our eyes. The river also tastes ‘pleasant sunrise’. This is a blend of gustatory and visual images. The river also consists of “green isles”. The poet repeatedly uses ‘green’ to bring about an effect of lush greenery which is quite contrary to the repeated term of ‘desert’ in the octave.

“And to the sea as happily dost haste.“

Though Keats wrote this poem in a very friendly sonnet, it is beautifully penned down with elevated language that is not only rich in meaning but in style, as well.

The River Nile

Nile River, Arabic Baḥr Al-Nīl or Nahr Al-Nīl, the longest river in the world, called the father of African rivers.The name Nile is derived from the Greek Neilos (Latin: Nilus), which probably originated from the Semitic root naḥal, meaning a valley or a river valley and hence, by an extension of the meaning, a river. The fact that the Nile—unlike other great rivers known to them—flowed from the south northward and was in flood at the warmest time of the year was an unsolved mystery to the ancient Egyptians and Greeks. The ancient Egyptians called the river Ar or Aur (Coptic: Iaro), “Black,” in allusion to the colour of the sediments carried by the river when it is in flood. Nile mud is black enough to have given the land itself its oldest name, Kem or Kemi, which also means “black” and signifies darkness. In the Odyssey, the epic poem written by the Greek poet Homer (7th century BCE), Aigyptos is the name of the Nile (masculine) as well as the country of Egypt (feminine) through which it flows. The Nile in Egypt and Sudan is now called Al-Nīl, Al-Baḥr, and Baḥr Al-Nīl or Nahr Al-Nīl.

The Nile River basin, which covers about one-tenth of the area of the continent, served as the stage for the evolution and decay of advanced civilizations in the ancient world. On the banks of the river dwelled people who were among the first to cultivate the arts of agriculture and to use the plow. The basin is bordered on the north by the Mediterranean; on the east by the Red Sea Hills and the Ethiopian Plateau; on the south by the East African Highlands, which include Lake Victoria, a Nile source; and on the west by the less well-defined watershed between the Nile, Chad, and Congo basins, extending northwest to include the Marrah Mountains of Sudan, the Al-Jilf al-Kabīr Plateau of Egypt, and the Libyan Desert (part of the Sahara).

The Nile River is also a vital waterway for transport, especially at times when motor transport is not feasible.

For example, during the flood season. Improvements in air, rail, and highway facilities beginning in the 20th century, however, greatly reduced dependency on the waterway.

Interesting facts about Nile

- The Rosetta Stone was discovered near Rosetta (Rash+d), a town located along the Nile River.

- Tourists can go white water rafting on the Nile River in Uganda.

- In 2013, a British journalist walked the length of the Nile in nine months.

- Ancient Egyptians worshipped a god of the Nile named Hapi.