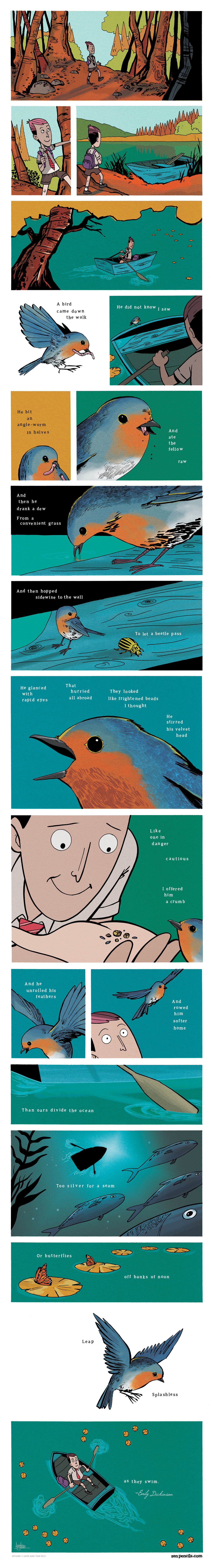

Poem

A Bird, came down the Walk –

He did not know I saw –

He bit an Angle Worm in halves

And ate the fellow, raw,

And then, he drank a Dew

From a convenient Grass –

And then hopped sidewise to the Wall

To let a Beetle pass

He glanced with rapid eyes,

That hurried all abroad

They looked like frightened Beads, I thought,

He stirred his Velvet Head.

Like one in danger, Cautious,

I offered him a Crumb,And he unrolled his feathers,

And rowed him softer Home

Than Oars divide the Ocean,

Too silver for a seam,

Or Butterflies, off Banks of Noon,

Leap, plashless as they swim.

Poetess

Emily Dickinson is one of America’s greatest and most original poets of all time. She took definition as her province and challenged the existing definitions of poetry and the poet’s work. Like writers such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Walt Whitman, she experimented with expression in order to free it from conventional restraints. Like writers such as Charlotte Brontë and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, she crafted a new type of persona for the first person. The speakers in Dickinson’s poetry, like those in Brontë’s and Browning’s works, are sharp-sighted observers who see the inescapable limitations of their societies as well as their imagined and imaginable escapes. To make the abstract tangible, to define meaning without confining it, to inhabit a house that never became a prison, Dickinson created in her writing a distinctively elliptical language for expressing what was possible but not yet realized. Like the Concord Transcendentalists whose works she knew well, she saw poetry as a double-edged sword. While it liberated the individual, it as readily left him ungrounded. The literary marketplace, however, offered new ground for her work in the last decade of the 19th century. When the first volume of her poetry was published in 1890, four years after her death, it met with stunning success. Going through eleven editions in less than two years, the poems eventually extended far beyond their first household audiences.

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson was born in Amherst, Massachusetts, on December 10, 1830 to Edward and Emily (Norcross) Dickinson. At the time of her birth, Emily’s father was an ambitious young lawyer. Educated at Amherst and Yale, he returned to his hometown and joined the ailing law practice of his father, Samuel Fowler Dickinson. Edward also joined his father in the family home, the Homestead, built by Samuel Dickinson in 1813. Active in the Whig Party, Edward Dickinson was elected to the Massachusetts State Legislature (1837-1839) and the Massachusetts State Senate (1842-1843). Between 1852 and 1855 he served a single term as a representative from Massachusetts to the U.S. Congress. In Amherst he presented himself as a model citizen and prided himself on his civic work—treasurer of Amherst College, supporter of Amherst Academy, secretary to the Fire Society, and chairman of the annual Cattle Show. Comparatively little is known of Emily’s mother, who is often represented as the passive wife of a domineering husband. Her few surviving letters suggest a different picture, as does the scant information about her early education at Monson Academy. Academy papers and records discovered by Martha Ackmann reveal a young woman dedicated to her studies, particularly in the sciences.

Summary

The speaker describes once seeing a bird come down the walk, unaware that it was being watched. The bird ate an angleworm, then “drank a Dew / From a convenient Grass—,” then hopped sideways to let a beetle pass by.

The bird’s frightened, bead-like eyes glanced all around. Cautiously, the speaker offered him “a Crumb,” but the bird “unrolled his feathers” and flew away—as though rowing in the water, but with a grace gentler than that with which “Oars divide the ocean” or butterflies leap “off Banks of Noon”; the bird appeared to swim without splashing.

Form

Structurally, this poem is absolutely typical of Dickinson, using iambic trimeter with occasional four-syllable lines, following a loose ABCB rhyme scheme, and rhythmically breaking up the meter with long dashes. (In this poem, the dashes serve a relatively limited function, occurring only at the end of lines, and simply indicating slightly longer pauses at line breaks.)

Commentary

Emily Dickinson’s life proves that it is not necessary to travel widely or lead a life full of Romantic grandeur and extreme drama in order to write great poetry; alone in her house at Amherst, Dickinson pondered her experience as fully, and felt it as acutely, as any poet who has ever lived. In this poem, the simple experience of watching a bird hop down a path allows her to exhibit her extraordinary poetic powers of observation and description.

Dickinson keenly depicts the bird as it eats a worm, pecks at the grass, hops by a beetle, and glances around fearfully. As a natural creature frightened by the speaker into flying away, the bird becomes an emblem for the quick, lively, ungraspable wild essence that distances nature from the human beings who desire to appropriate or tame it. But the most remarkable feature of this poem is the imagery of its final stanza, in which Dickinson provides one of the most breath-taking descriptions of flying in all of poetry. Simply by offering two quick comparisons of flight and by using aquatic motion (rowing and swimming), she evokes the delicacy and fluidity of moving through air. The image of butterflies leaping “off Banks of Noon,” splashlessly swimming though the sky, is one of the most memorable in all Dickinson’s writing.

Analysis

This poem is based on a very ordinary incident. A bird eats a worm and flies away refusing a crumb offered by the poet who turns this apparently commonplace incident into a poetic masterpiece with her rich imagination.

The poem begins with the line:”A bird came down the Walk-“. Do you find anything unusual in this line? Well, to me, it strikes rather odd. For one thing, we normally say ‘a bird flied down’. It seems the poet wanted to attribute some human quality to the bird. This is further reinforced by the word “Walk”. A walk, as a noun, refers to a route or lane used for leisurely walking. It is similar to a jogging track used by people for jogging or walking. Thus, the bird is compared to a person who is having a lesurely walk in the evening. This creates slight humour which contrast sharply with the tension created by the third and fourth lines where the bird “bit an Angleworm in halves/And ate the fellow, raw.”

Further, the bird’s apparently ‘civilized’ behaviour contrasts sharply with his ‘wild’ behaviour in eating the Angleworm ‘raw’. The word “raw” gets an additional weight because it rhymes with the word “saw” in the second line. Whether it is ‘civilized’ or ‘wild’, this natural behavior of the bird who is so far unaffected by the presence of the speaker as the poet says “He did not know I saw-“. Further, the word “fellow” contributes to the playful tone. Obviously, the poet is not ‘shoked’ by the bird’s act. In fact, he presents the nature as it is, both its beauty and wildness, as an observer. The poet may be also suggesting the cruelty hidden behind the façade of civility in the society in this stanza. The rhyming pattern abcb continues in the subsequent stanzas.

Now let’s look at the first two lines of the second stanza:

And then he drank a Dew

From a convenient Grass—

The bird’s human-like quality is further emphasized in these two lines. Normally we, humans, take pride in the fact that we are superior to all other species of animals. However, the poet seems to suggest in these lines that animals are no less superior to humans, in their own way. The use of the indefinite article ‘a’ also deserves our attention here. Normally we expect ‘a drop of dew’ in the first line. However, the use of ‘a Dew’ together with the alliteration of the‘d’ sound seem to enhance the poise and refinement of the bird. The sparkling beauty of the dew also symbolizes the beauty of the pristine nature unspoilt by industrialization. In the next line the poet uses an unusual phrase: ‘a convenient Grass’. The word ‘Grass’ (again ‘a’ glass) rhymes strongly with ‘glass’ which suggests an echo-pun on glass. This creates a picture of a person drinking from a glass. Further, the bird finds his food and drinks easily, may be more easily than humans. These lines also remind me about another poem by D.H. Lawrence. In this poem called ‘Snake’, Lawrence, the narrator is mesmerized by the graceful behavior of the snake. This is how he describes the way the snake drank water from his water trough:

He sipped with his straight mouth,

Softly drank through his straight gums, into his slack long body,

Silently.

The soft alliteration of the‘s’ sound together with the slow, graceful rhythm creates a tantalizing effect.

This graceful behaviour of the bird in our poem is further highlighted in the next two lines:

And then hopped sidewise to the Wall

To let a Beetle pass—

Here, the bird gets aside to let a beetle pass- a very courteous movement indeed! Our bird seems to know his manners! Doesn’t this suggest that animals have their own ‘etiquette’? Surely, the poet seems to be marvel ing at the beauty and gracefulness of the untamed nature in these lines. Further, in these two stanzas, the poet seems to anthropomorphize the bird. In other words she attributes human qualities to the bird.

You might also wonder why the poet has used dashes in these lines. The poem is written in iambic trimeter in the first three lines and iambic tetra meter in the third line in every stanza except the last stanza and the dashes are occasionally used to break the rhythm. This breaking of the rhythm suggests that the bird is uneasy and even unsteady in the ground as its natural habitat is the sky.

In the third stanza, the poet describes the bird’s frightened behavior after eating the worm:

He glanced with rapid eyes

That hurried all around—

They looked like frightened Beads, I thought—

He stirred his Velvet Head

The bird’s glancing around with rapid, frightened eyes suggests both caution and fear. As some critics suggest, it is because the bird feels guilty and he is afraid of the consequences of his ‘cruel’ act. I don’t agree with this idea because it is quite natural for a bird to eat a worm. Surely we don’t expect them to buy sausages from a supermarket? Rather, it may be a fear common to all animals since they are constantly exposed to various dangers, especially from predators. In the famous Novel ‘Village in the Jungle’ (of Beddegama), Leonard Woolf says:

‘For the rule of the jungle is first fear, and then hunger and thirst. There is fear everywhere…’

Even human beings are afflicted with three main types of fear, according to Rathana Sutta: ‘sambutam tividham bhayam’.

The poet cmpares the bird’s eyes to ‘frightened bead’. The poet personifies the bead in this line. A bead with its tiny hole and rolling motion is a stunning image to describe bird’s eyes as it is light and lustrous. However, it also suggests a certain hard quality in the bird. This contrasts sharply with the ‘velvet head’ which suggests certain fluffiness and beauty.

The Fourth stanza opens with the line:

Like one in danger, Cautious,

We are tempted to ask ‘what is the danger?’and the reason for his being ‘cautious’. Well, as I mentioned before, a bird’s natural domain is the sky and thus, he tends to behave rather clumsilly and nervously in the ground. As such, the above line aptly describes his behaviour in the ground. The next line marks the turning point in the poem:

I offered him a Crumb,

So far, the poet was just observing the bird as a passive onlooker. But now she intervenes in the action and offers him a crumb. The poet’s action may be also symbolic. It might symbolize man’s intervention with nature and perhaps, his attempt to tame the nature. The action of offering a crumb is also suggestive of the man’s condescending attitude towards animals. However, instead of eating the crumb, the bird takes flight immediately:

And he unrolled his feathers,

And rowed him softer Home –

The bird contemptuously rejects the crumb and begins to fly towards home. The bird’s action might symbolize man’s futile attempt to tame the nature. These two lines also begin a series of spectacular images used to describe the bird’s flight. Once in the sky, the bird begins to appear in all its glory and splendour as it is his natural domain. The smooth actions of ‘rolling’ and ‘rowing’ together with the assonance of the ‘o’ sound contribute to the fluidity of the movement. The bird takes off into the sky with so much ebullience ‘like a duck takes to water’, as the saying goes.

The last stanza is the most memorable one in the poem. The poet savours image after image of exquisite beauty which describe the breathtaking flight of the bird:

Than Oars divide the Ocean,

Too silver for a seam,

Or Butterflies, off Banks of Noon,

Leap, plashless as they swim.

In the first line, the bird’s feathers are compared to the oars which are used to propel a boat forward. The movement of oars creates hardly any disturbance in the water; likewise, the bird’s wings too do not make any disturbance or impact on the sky; Its flight is ‘seamless’. It does not leave any mark in the sky just like oars which do not leave any ‘seam’ or mark on the water. The comparison between the ocean and the sky is quite striking. The bird’s flight may also symbolize perfect harmony in nature. The assonance of the ‘o’ sound in the first line and the alliteration of the‘s’ sound in the second line also contribute to the lyrical beauty of the lines. The word ‘silver’ has the connotations of gracefulness and glamour in addition to beauty.

In the next two lines, the bird’s flight is compared to another scene of breathtaking beauty: that of butterflies fluttering in the banks of a river. First he compared to bird’s flight to an inanimate object (oars) and now he compares them to an animate thing (butterflies). The poet makes an implied comparison between the butterflies and fish when she says ‘they swim’. It again suggests the smoothness and the gracefulness of the bird’s flight through the sky. ‘Plashless’, a rather uncommon word, means smooth or fluid.

Through this poem, the poet seems to highlight the both the beauty and the danger of the untamed nature. Another famous poem called ‘A narrow Fellow in the Grass’ also deals with a similar theme.

Hope you have enjoyed my analysis. As you can see, appreciating a poem doesn’t mean just explaining the poem and giving a note covering its theme and techniques only. Instead, we must pay close attention to the words used by the poet and how he has organized them create a particular effect and how it contributes to the overall meaning. In short, a poem should be treated as a living thing with a soul.

Literary Devices

There are many poetic devices in Emily Dickinson’s “A Bird come down the Walk-” including metaphor, simile, personification, and alliteration.

Metaphor is present in the third stanza.

He stirred his Velvet Head.

This is a metaphor because the narrator compares the bird’s head to velvet without the use of “like” or “as.” This emphasizes the texture of the bird’s head and creates an idea of softness.

Simile is present in the third stanza.

He glanced with rapid eyes

That hurried all around-

They looked like frightened Beads, I thought-

This is a simile because the narrator compares the bird’s eyes to beads. This is also personification because the beads are “frightened,” and as we know, beads are inanimate objects and cannot be frightened.

Another simile extends through the fourth and fifth stanzas.

And he unrolled his feathers

And rowed him softer home

Than Oars divide the Ocean

That simile compares the feathers to oars dividing the ocean. We can then imagine the motion of the wings and the slickness of the feathers.

Alliteration is also present throughout the poem. Alliteration is the repetition of the beginning sound of a word.

Too silver for a seam-

Or Butterflies, off Banks of Noon

This quote contains two different moments of alliteration – in the first line with the letter “s” and in the second line with the letter “b.”