Poem

“Farewell to barn and stack and tree,

Farewell to Severn shore.

Terence, look your last at me,

For I come home no more.”

“The sun burns on the half-mown hill,

By now the blood is dried;

And Maurice amongst the hay lies still

And my knife is in his side.”

“My mother thinks us long away;

‘Tis time the field were mown.

She had two sons at rising day,

To-night she’ll be alone.”

“And here’s a bloody hand to shake,

And oh, man, here’s good-bye;

We’ll sweat no more on scythe and rake,

My bloody hands and I.”

“I wish you strength to bring you pride,

And a love to keep you clean,

And I wish you luck, come Lammastide,

At racing on the green.”

“Long for me the rick will wait,

And long will wait the fold,

And long will stand the empty plate,

And dinner will be cold.”

Glossary

barn – a large cottage built in the farm for storage purposes.

stack – a heap of something. (probably, in this poem, it would be a heap of hay)

shore – the boundaries of the country side

half-mown – grass that has been left half-cut.

scythe – a tool used for cutting crops such as grass or corn, with a long curved blade at the end of a long pole attached to one or two short handles.

rake – an implement consisting of a pole with a toothed crossbar or fine tines at the end, used especially for drawing together cut grass or smoothing loose soil or gravel.

rick – a stack of hay, corn, straw, or similar material, especially one formerly built into a regular shape and thatched.

fold – a small enclosure for livestock (especially sheep or cattle), which is part of a larger construction.

Severn Shore – a small village by the side of the River Severn, which is the longest river in the United Kingdom.

Lammastide – Lammas Day (Anglo-Saxon hlaf-mas, “loaf-mass”), is a holiday celebrated in some English-speaking countries in the Northern Hemisphere, usually between 1 August and 1 September. It is a festival to mark the annual wheat harvest, and is the first harvest festival of the year.

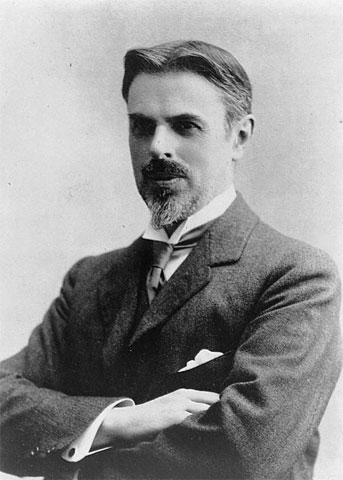

A.E Housman

Alfred Edward Housman was born in Fockbury, Worcestershire, England, on March 26, 1859, the eldest of seven children. A year after his birth, Housman’s family moved to nearby Bromsgrove, where the poet grew up and had his early education. In 1877, he attended St. John’s College, Oxford and received first class honours in classical moderations.

Housman became distracted, however, when he fell in love with his roommate Moses Jackson. He unexpectedly failed his final exams, but managed to pass the final year and later took a position as clerk in the Patent Office in London for ten years.

During this time he studied Greek and Roman classics intensively, and in 1892 was appointed professor of Latin at University College, London. In 1911 he became professor of Latin at Trinity College, Cambridge, a post he held until his death. As a classicist, Housman gained renown for his editions of the Roman poets Juvenal, Lucan, and Manilius, as well as his meticulous and intelligent commentaries and his disdain for the unscholarly.

Housman only published two volumes of poetry during his life: A Shropshire Lad (1896) and Last Poems (1922). The majority of the poems in A Shropshire Lad, his cycle of 63 poems, were written after the death of Adalbert Jackson, Housman’s friend and companion, in 1892. These poems center around themes of pastoral beauty, unrequited love, fleeting youth, grief, death, and the patriotism of the common soldier. After the manuscript had been turned down by several publishers, Housman decided to publish it at his own expense, much to the surprise of his colleagues and students.

While A Shropshire Lad was slow to gain in popularity, the advent of war, first in the Boer War and then in World War I, gave the book widespread appeal due to its nostalgic depiction of brave English soldiers. Several composers created musical settings for Housman’s work, deepening his popularity.

Housman continued to focus on his teaching, but in the early 1920s, when his old friend Moses Jackson was dying, Housman chose to assemble his best unpublished poems so that Jackson might read them. These later poems, most of them written before 1910, exhibit a range of subject and form much greater than the talents displayed in A Shropshire Lad. When Last Poems was published in 1922, it was an immediate success. A third volume, More Poems, was released posthumously in 1936 by his brother, Laurence, as was an edition of Housman’s Complete Poems(1939).

Despite acclaim as a scholar and a poet in his lifetime, Housman lived as a recluse, rejecting honors and avoiding the public eye. He died on April 30, 1936, in Cambridge.

Analysis

“Farewell to barn and stack and tree,

Farewell to Severn shore.

Terence, look your last at me,

For I come home no more.”

While bidding farewell to his familiar surroundings, the speaker brings out the feeling of urgency in him. He bids farewell to his whole village, probably (Severn shore). And he requests his brother whom he has just killed, to look at him for the last time. The speaker here addresses to a third person referred by the name “Terence.” Even though we are not sure about who this third person could be, by the words addressed to this Terence we understand that the speaker has decided not to return to this his own place. While we attempt to guess who this person could be, we may end up with conclusions which are depending on our perspectives. Either a neighbor, a friend of these siblings or the mistress for whom the brothers fought for. The first stanza itself provides this urgency and suspense which leads the reader to go further and inquire about this incident in the following stanzas.

“The sun burns on the half-mown hill,

By now the blood is dried;

And Maurice amongst the hay lies still

And my knife is in his side.”

This is the first place where the reader realizes that this urgent bidding of farewell is followed by a a murder. The ‘sun burn’ being mentioned shows that it is probably noon time. While the ‘half-mown hill’ reminds us of the farming background and the country side, it is followed by an expression that it was a bloody murder, and it had happened somewhere early in the day, so that the blood is dried. The victim’s name is introduced – Maurice. The name being mentioned than any other word to refer to the dead person in the midst of this feeling of guilt shows that they were very close to each other. It brings in that personal attachment the assailant had with the killed. And he had committed the murder with his knife, which he had left near the person in a hurry to evacuate from the place where he had murdered.

“My mother thinks us long away;

‘Tis time the field were mown.

She had two sons at rising day,

To-night she’ll be alone.”

This stanza again proves the point that they are brothers; the murderer and the victim. The speaker remembers his family, his mother, and obviously he would have found it an impossible thing to face her ever again. He imagines with guilt how their mother would be waiting for her sons who had set out of home that morning to mow the fields. He goes further in empathizing the pain that their mother is going to go through. That morning their mother had two sons in her side, and today when the day ends one of her sons is killed and the other has gone far away, running away from home in fear and guilt, unable to face the consequences of what he has done. This stanza evokes in the reader, not just the feelings of the speaker, but also the feelings of their mother. It creates empathy.

“And here’s a bloody hand to shake,

And oh, man, here’s good-bye;

We’ll sweat no more on scythe and rake,

My bloody hands and I.”

Remembering the times he and his brother have worked together, shared moments of both accomplishments and failures, as men who live together under the same roof in the same family, the speaker is even unable to say a proper heart felt goodbye. He would have never expected to bud such a farewell to his own brother, with such blood stained hands. He remembers that those moments are not going to be there again.

“I wish you strength to bring you pride,

And a love to keep you clean,

And I wish you luck, come Lammastide,

At racing on the green.”

“Long for me the rick will wait,

And long will wait the fold,

And long will stand the empty plate, And dinner will be cold.”

The last two stanzas together, provide the great things that this speaker who is bidding farewell is going to miss in future. Both social and personal. As bids farewell, he remembers the festivals and the celebrations that he had been celebrating with his family. We are with a question here. Why would he “wish” something for the dead person? Especially for the Lammastide or the racing on the green? Probably it was the speakers imaginary thinking that his brother would at least enjoy ad cherish the same things in his life after death.

He remembers all that he is leaving behind and going and also remembers that it going to be a different life for him from now on. A different profession for survival, somewhere far away from home. To make it more personal, he is also with the fear that he would even end up somewhere without the basic necessities for his life. To show that his return is never possible, he mentions the “long wait.” But the phrase also gives the reader a little bit of hope; a return after the suffering of guilt is over.

Who is Terrence?

Notice that the whole poem is in quotation marks. Terence is the guy who is repeating to us what his friend said to him. The friend confesses to having murdered his own brother, and now he’s either going to commit suicide or else turn himself in to the police and be executed; either way, he’s saying good-bye forever to Terence, and now Terence is telling us what his friend said.

The poem is from a whole book that Housman, the author, originally called “Poems of Terence Hearsay.” Terence is the fictional speaker of most of the poems. He’s an average guy who lives on a farm in rural Shropshire and tells us stories (mostly very dark and depressing ones) about his own life and his neighbors.